Cloudpipe: Compute on Demand

30 January 2015

When you want to execute a long-running or massively parallel process in a persistent way, you have a few options. You can launch a server, install a bunch of software, and stitch things together with cron. Or, you can install a Hadoop cluster, rewrite everything from the ground up to use map-reduce or Spark or another powerful concurrency framework, and orchestrate your job with that toolkit.

Those options all have their place, but sometimes, all you want to do is write some code and run it somewhere. No server spin-up, no system administration, no patches and security updates. Kyle Kelley and I spent a few weeks around the holidays putting together an open-source project called “Cloudpipe” to accomplish exactly this. Today, we have a proof of concept we can run that successfully executes jobs, and we’re hard at work filling in the blanks in the architecture and putting together a real deployment.

Using it

To start, we chose to target an existing client SDK, Python’s multyvac, which was nice for a few reasons:

- It gave me a concrete spec to target while I was mapping out the endpoints for the API server. This saved us a lot of bikeshedding in the early days.

- It let me start backend-first and test things with real code, just as a user would experience them. Otherwise, I would have had to use awkward

curlscripts until we could design and put together a decent SDK. - In theory, people are already using the SDK. (If that search is any indication, though, we should have stuck with its predecessor, cloud, instead.)

As a result, the only client SDK that exists today is for Python (and Python 2, at that). That’s going to change, though - we’ve been planning to write our own client for Python and Shaunak Kashyap is already working on an SDK for node.js. We’re also likely to diverge more and more from multyvac as we move on.

Once you have an account running on a cluster somewhere, you can install multyvac with:

pip install multyvac

Then, you can submit functions as jobs:

import multyvac

# Connect to the cluster

multyvac.config.set_key(api_key='username',

api_secret_key='54321',

api_url='https://somewhere/v1')

def add(a, b):

return a + b

# Submit the function as a job. Args and kwargs will be

# passed to it server-side.

jid = multyvac.submit(add, 3, 4)

# Use the job ID to get a Job object...

job = multyvac.get(jid)

# ... and use the Job object to get the result.

# This call will block until the result is ready.

result = job.get_result()

Multyvac uses some neat pickling tricks to send your function over the wire: you can actually send closures, or code that references external libraries, and it’ll work. Other languages’ SDKs may not be able to pull the same range of tricks, depending on how evil each runtime lets us be, but they’ll support the same basic idea.

One important thing to notice is that the way work is submitted to the API is completely language-agnostic: it’s a contract between the SDK and the base Docker image that’s invoked on the server. The Cloudpipe API speaks strictly in terms of POSIX things: command and arguments, environment variables, and standard input, output and error streams.

How it works

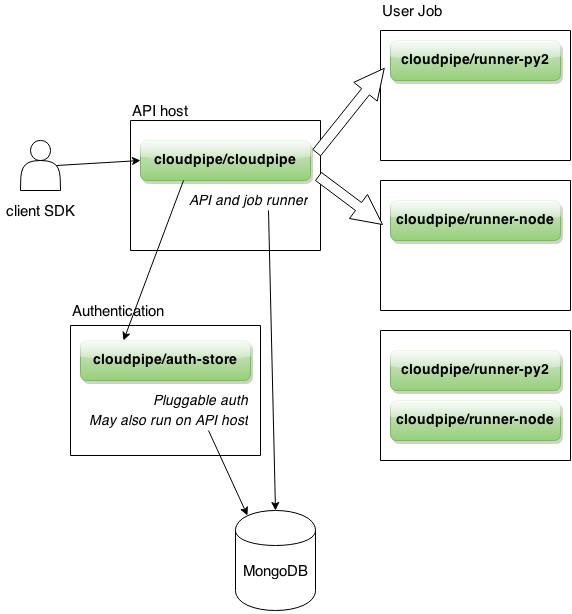

Behind that URL, Cloudpipe is built from a small set of parts, all written in Go.

The API server is an HTTPS server that hosts a JSON API. It’s a fairly thin layer that performs CRUD operations on job models persisted in a MongoDB instance.

We’re using Mongo because it’s convenient for us, by the way: storage operations are performed through an interface, so implementations built on other databases are possible and welcome.

The job runner is a separate goroutine within the same process as each API server. It polls a queue of submitted jobs in MongoDB and uses the go-dockerclient library to launch each one. The runner creates a container from the requested image, attaches to its stdin, stdout and stderr, and starts it. Any provided stdin is fed in to the process; stdout and stderr are collected and used to update the job’s model in Mongo as it executes.

In development mode, the container is launched on the same server that you’re running everything else on, but in any “real” setting user jobs should run on a different machine. We’re planning to use swarm as a way to manage submitting jobs to a cluster.

Under the hood, the API server talks to a pluggable authentication server over HTTPS on an internal network, secured with a closed network of TLS credentials – meaning, the authentication server only accepts connections from clients who offer certificates signed by an internal certificate authority that we (the cluster operators) control.

The authentication protocol consists of two calls. The reference authentication server, cloudpipe/auth-store, implements this with interally-stored usernames and passwords. It also offers an externally-facing API that can be used to create and manipulate accounts, but that’s all extra. We can also plug in an authentication backend that talks to Rackspace identity to use Rackspace credentials, for example, or implement one that speaks OAuth.

A runner image is used to spawn a container that understands what the SDK is sending in and executes it as a non-root user. The Python one unpickles stdin and calls the resulting function, writing the result to a fixed location on the filesystem. Not bad for four lines of code.

Finally, all of these services are themselves running in Docker containers, because why not.

Here’s how it all fits together:

Into the Future

What’s happening next? To begin with, we’re working on a simple web UI to provide a friendlier way to get your API key, create user accounts, monitor your jobs and so on. Shaunak is working on our first non-Python client SDK, for Node.js, and I’d like to start laying the groundwork for a Ruby SDK Soon (tm).

I’m also interested in extending the base API to support:

-

Configurable sources of input and output. Run jobs to and from a Cloud Files container, or a database, or mount volumes into your container’s filesystem from a block volume.

-

Constructing derived images from the provided base images.

-

Job lifecycle management. Run jobs on a schedule. Save jobs and re-run them by name.

Additionally, we’re going to start writing some Ansible roles to help bootstrap servers as API hosts, authentication hosts, or user job hosts.

Want to get involved? Dive right in – Pull requests are always welcome!